Name of Monument:

Chefchaouen Kasbah

Location:

110 km from Tangier and 60 km from Tetouan, Chefchaouen, Morocco

Date of Monument:

Hegira 10th–11th centuries / AD 15th–16th centuries

Period / Dynasty:

Wattasid; Sa'did

Patron(s):

Mulay ‘Ali ibn Musa ibn Rashid.

Description:

Under the Wattasids (AH 9th–10th / AD 15th–16th centuries) and concomitant with the progress of the Christian Reconquista of al-Andalus, Morocco was exposed to numerous Spanish and Portuguese attacks.

In AH 875 / AD 1471, the year that Tangier and Asilah were taken by the Portuguese, the Sharif Mulay Ali ibn Rashid, a descendant of the great AH 6th / AD 12th century Moroccan saint Mulay 'Abd al-Salam ibn Mshish who claimed to be from the first Muslim dynasty in Morocco, the Idrisids (AH 2nd–4th / AD 8th–10th centuries), took the initiative, in response to the weakness of the central power, to create a fortified town to defend and protect the region in which he was born in the Rif mountains.

Built for the purpose of jihad, the fortress of Banu Rashid quickly became the centre of a genuine principality, with independent political power and influence beyond the confines of the Rif area.

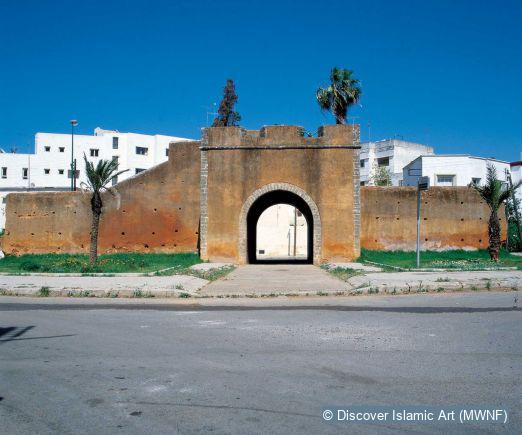

A new town, named Chefchaouen ('the horns' in Berber, in reference to the mountain peaks in the surrounding area) was built to the southwest of the kasbah/fortress in an Andalusian–Maghrebian style within powerful ramparts flanked by towers and interrupted by seven gateways. It grew and prospered, giving refuge to some of the waves of Muslim and Jewish migrants from al-Andalus who were expelled from Spain following the Christian Reconquista of AD 1492.

The kasbah, which was both a permanent military encampment and a seigniorial residence, has a curtain wall flanked with 11 towers, the main tower being of more recent construction (early AH 10th / AD 16th century).

This practically square-plan tower (7.70 m by 7.40 m) rises over three storeys:

- On the ground floor, there is a room approximately 5 m wide with a central octagonal pillar from which four perpendicular semi-circular arches spring. The ceiling of this room consists of four brick-built surbased domes on squinches.

- On the first floor, the space is divided into two rectangular rooms by a cross beam supported on a small pillar.

- The top floor consists of a terrace with a crenelated parapet.

The gateway in the façade opposite the main tower, which leads to the suq via a bent passageway, is low and narrow and crosses a large room measuring 8.30 m by 4 m.

In the northeast corner of the kasbah, the old palatial area, whose current form is the result of later building work, is now home to a museum and a centre of Andalusian studies.

The al masjid al-a'dam mosque ('the very great mosque') built next to the kasbah was extended in the AH 11th / AD 17th century. With the exception of its main entrance, the building is entirely undecorated and is only noteworthy for its octagonal minaret, characteristic of the north of Morocco.

In addition to its defensive and political functions, Chefchaouen has historically been a religious focus for the region, and even the country as a whole. Consequently there are no fewer than 20 mosques and 28 zawiya (religious teaching extablishments) and mausoleums, hence its being known as the blessed town (al madina as-saliha).

Morocco's power diminished during the AH 9th–10th / AD 15th–16th centuries, which boosted the Christian Reconquista and enabled the Portuguese to occupy Tangier. At this time, Mulay Ali ibn Rashid built a fortified town in the Rif, which became the seat of a genuine principality. A new town, Chefchaouen, grew up nearby and became home to many of the Muslims and Jews expelled from Spain.

Fortress, military encampment and seigneurial residence – the kasbah has an outer wall with eleven towers and a mosque with an octagonal, plain minaret.

The palace area has been converted into a museum.

How Monument was dated:

Historical and hagiographic sources quoted by scholars of Chefchaouen date the construction of the fortified enclosure to the last third of the 9th / 15th century. The main tower was rebuilt in its current form approximately half a century later.

Selected bibliography:

Colin, G. S., “Shafshawan”, Encyclopédie de l'Islam, IV, 1926, p.263 et seq.

Gozalbes Busto, G., “Gurazim: cuña de Xauen. Contribución al estudio de la historia de Marrueccos”, Cuadernos de la Biblioteca Española de Tetuán, 17–18, 1978, pp.83–98.

Touri, A., Bazzana, A., Cressier, P., “La Qasbah de Shafshawan”, Castrum 3, guerre, fortification et habitat dans le monde méditerranéen, Madrid; Rome, 1988, pp.153–62.

Andalusian Morocco: A Discovery in Living Art, pp.148–56.

Citation of this web page:

Kamal Lakhdar "Chefchaouen Kasbah" in Discover Islamic Art, Museum With No Frontiers, 2025. 2025.

https://islamicart.museumwnf.org/database_item.php?id=monument;ISL;ma;Mon01;30;en

Prepared by: Kamal LakhdarKamal Lakhdar

Linguiste et sociologue de formation, c'est en autodidacte que Kamal Lakhdar s'est adonné aux études d'histoire du Maroc et du monde arabo-musulman, en axant tout spécialement ses recherches sur l'histoire de Rabat.

Sa carrière de haut fonctionnaire l'a conduit à occuper des fonctions de premier plan auprès de différents ministères. Il a notamment été membre du cabinet du ministre de l'Enseignement supérieur, conseiller du ministre des Finances, conseiller du ministre du Commerce et de l'Industrie, directeur de cabinet du ministre du Tourisme, chargé de mission auprès du Premier ministre et directeur de cabinet du Premier ministre.

Parallèlement, Kamal Lakhdar mène des activités de journaliste et d'artiste peintre – il a d'ailleurs été membre du Conseil supérieur de la Culture.

Copyedited by: Margot Cortez

Translation by: Laurence Nunny

Translation copyedited by: Monica Allen

MWNF Working Number: MO 39

RELATED CONTENT

Related monuments

On display in

Exhibition(s)

Download

As PDF (including images) As Word (text only)

Back

Back