Name of Monument:

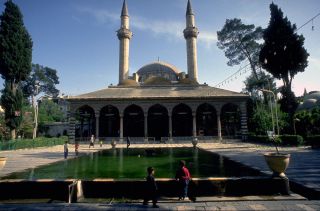

Takiyya al-Sulaymaniyya

Location:

Damascus, Syria

Date of Monument:

Hegira 962–74 / AD 1554/5–1566/7

Architect(s) / master-builder(s):

The Turkish architect Sinan; the master builder was a Persian called Mullah Agha, partly substituted by Turkish building inspectors, one of them called Mustafa.

Period / Dynasty:

Ottoman

Patron(s):

Sultan Suleyman ‘the Magnificent’ I (r. AH 926–74 / AD 1520–66).

Description:

Together with a madrasa, the Takiyya al-Sulaymaniyya was erected on the meadow belonging to a former Zangid parade ground, the Maydan al-Akhdar, located about 800 m west of the Old City of Damascus on the southern shore of the Barada River. It is the spot where once the Qasr al-Ablaq, the palace belonging to Sultan Baybars (r. AH 658–75 / AD 1260–77) stood, and where Timur resided during his attack on Damascus. The takiyya functioned as an inn for the accommodation of pilgrims where food was served, gratis.

The whole complex was surrounded by an enclosure wall; to the west of the enclosure there was a vast area that was used as a tent encampment for pilgrims. From the main entrance on the east side, the visitor steps into the large courtyard where a central rectangular pool served as a meeting place. The mosque, preceded by a double portico, is by its twin minarets announced as a royal foundation. A row of cells is placed along either side of the courtyard while opposite the mosque is the imaret flanked by two long refectories along the east and west walls, each covered with 14 domes. Between them a large kitchen is preceded by a portico, the purpose of which may have been to offer shade to the pilgrims queuing for food, but which also gives a sort of splendour to the kitchen area. On each side of the kitchen, there are two twin-domed smaller rooms, which may have served as stores or dining chambers for the leaders of the Hajj. The enclosure to the north of the imaret is provided with a small entrance used by servants and to take in deliveries.

Immediately after the Ottoman conquest and up until the AH mid-10th / AD mid-16th century, the local – and likewise modest – building activity continued in a traditional way indicating a tolerant takeover of power. This is manifested not only by the fact that Mamluk governors were re-instated to office, but also by the employment of Damascene master architect, Shihab al-Din Ahmad ibn al-Attar who, for example, was employed by Sultan Selim I for the renewal of the funeral mosque of the renowned Sufi, Ibn Arabi in Salihiyya. Although the takiyya was planned by the Turkish master architect of the Sultan, Sinan (AH 895–996 / AD 1490–1588), he did not supervise the work personally but delegated much of it to a local subordinate. Native workmen were consulted, leaving their fingerprints on details of the décor such as the horizontal rows of alternating dark-and-light stone walls (,'en');" style="text-decoration: underline;">ablaq). The tiles also show the characteristics of locally produced Damascene tiles, referring to the Turkish production of Iznik, but paler in colour.

The complex's location at a prominent place amidst the long-distance trade and pilgrimage routes made it popular stop-off point for pilgrims from all over the Ottoman Empire and beyond, who were accommodated before continuing to the Holy places in the Arabian Peninsula. Its characteristically Ottoman style, with porticoes and dominant use of cupolas and pencil-shaped minarets make it a clear display of Ottoman supremacy.

Several hundred metres before the city gates, one of the early Ottoman sultans, Sulayman the Magnificent (r. AH 926–74 / AD 1520–66), built a hospice for pilgrims who gathered in Damascus from all over the empire before turning south towards Mecca. The complex comprises a mosque, a kitchen, dormitories and a madrasa. For the first time, Ottoman features such as multiple cupolas and pencil-shaped minarets appear in Damascus, doubtless meant as architectural symbols of Ottoman supremacy. This is the only building in Bilad al-Sham (Greater Syria) designed by the celebrated Turkish architect Sinan.

How Monument was dated:

Several Arabic sources discuss the building activities of Sultan Suleyman (see Rihawi, 1957, p.132) for a detailed list of these sources.

Selected bibliography:

Goodwin, G., A History of Ottoman Architecture, London, 1971, p.256ff.

Kafesçioğlu, C., “'In the Image of Rum': Ottoman Architectural Patronage in Sixteenth-century Aleppo and Damascus”, Muqarnas, 16, 1999, pp.70–96.

Meinecke, M., “Die osmanische Architektur des 16. Jh”, Damaskus, Fifth International Congress of Turkish Art, Budapest, 1978, pp.580–2, p.590.

Rihawi, Abd al-Qadir, “al-Abniya al-Athariyya fi Dimashq 1: al-Takiyya wa-al-madrasa al-Sulaymaniyyatan bi-Dimashq [The Archaeological Buildings of Damascus: The Takiyya and the School of Sulayman in Damascus]”, Annales Archéologiques de Syrie, 1957, pp.125–34.

Wulzinger, C., and Watzinger, C., Damaskus, die islamische Stadt, Berlin–Leipzig, 1924, pp.102–14.

Citation of this web page:

Verena Daiber "Takiyya al-Sulaymaniyya" in Discover Islamic Art, Museum With No Frontiers, 2025. 2025.

https://islamicart.museumwnf.org/database_item.php?id=monument;ISL;sy;Mon01;19;en

Prepared by: Verena DaiberVerena Daiber

Verena Daiber is an historian of Islamic art an archaeology. She studied Near Eastern Archaeology and Arabic Literature at the Free University of Berlin. After her employment as research associate at the German Archaeological Institute in Damascus she obtained her PhD at the University of Bamberg in 1991 on the public architecture of Damascus in the 18th century. Since 2017 she is the curator of the Bumiller Collection / Bamberg University Museum of Islamic Art that holds Islamic metalwork from the Persian world. After publishing on ceramics, architecture and imagery of the central Arabic lands, she works on the development and publishing of the Bumiller Collection.

Copyedited by: Mandi GomezMandi Gomez

Amanda Gomez is a freelance copy-editor and proofreader working in London. She studied Art History and Literature at Essex University (1986–89) and received her MA (Area Studies Africa: Art, Literature, African Thought) from SOAS in 1990. She worked as an editorial assistant for the independent publisher Bellew Publishing (1991–94) and studied at Bookhouse and the London College of Printing on day release. She was publications officer at the Museum of London until 2000 and then took a role at Art Books International, where she worked on projects for independent publishers and arts institutions that included MWNF’s English-language editions of the books series Islamic Art in the Mediterranean. She was part of the editorial team for further MWNF iterations: Discover Islamic Art in the Mediterranean Virtual Museum and the illustrated volume Discover Islamic Art in the Mediterranean.

True to its ethos of connecting people through the arts, MWNF has provided Amanda with valuable opportunities for discovery and learning, increased her editorial experience, and connected her with publishers and institutions all over the world. More recently, the projects she has worked on include MWNF’s Sharing History Virtual Museum and Exhibition series, Vitra Design Museum’s Victor Papanek and Objects of Desire, and Haus der Kulturen der Welt’s online publication 2 or 3 Tigers and its volume Race, Nation, Class.

MWNF Working Number: SY 23

RELATED CONTENT

Related monuments

Islamic Dynasties / Period

On display in

Exhibition(s)

The Table Is Set

Social Life | Food as a Bond of Communal IdentityDownload

As PDF (including images) As Word (text only)

Back

Back