Mudéjar Art

|

The most noteworthy aspect of Mudéjar art is its singularity. It cannot be compared to any other artistic style, whether Islamic or Christian, as it arose from a set of historical circumstances that were unique to the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Ages.

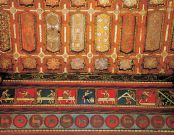

Effectively, when the Christian kings re-conquered the lands of al-Andalus, they had some difficulty repopulating immediately, and consequently they allowed Muslims to stay in the newly conquered territories, retaining their religion, language and system of laws. These Mudéjars, Muslims in Christian lands, joined the new society, worked for its elite and contributed Islamic customs and art, whose colours, exoticism, luxury and refinement fascinated Christian kings and noblemen. Mudéjar art is easily recognisable by the perfect integration of the materials used (brick, plaster, wood and ceramic), the specific techniques used to work them and the decorative motifs taken from Islamic aesthetics. Mudéjar art should be seen as the survival of Islamic art in Christian society, although this interpretation is only valid from a formal point of view as the Islamic decorative and structural forms in Mudéjar art express the thoughts and values of Christian and not Islamic culture. Elements of Islamic art combined perfectly with the Western artistic tradition to create a new form which differed depending on whether the combination was based on Romanesque, Gothic or Renaissance art. As a result, strictly speaking, Mudéjar art did not belong to either the Islamic or Christian artistic traditions. A link between two cultures, Mudéjar art became the artistic expression of a complex society in which Jews, Christians and Muslims lived side by side. This makes it a unique phenomenon in the history of art. The Mudéjar style declined during the AH 10th / AD 16th century and finally disappeared with the expulsion of the Moriscos in 1017 / 1609. Nonetheless, Mudéjar culture continued to satisfy the taste for a sort of 'Baroque style' until the advent of Baroque itself. |

Cathedral of Santa Maria Second half of the 13th century to 1538 Mudéjar Teruel, Spain  Seville Citadel 13th-15th centuries Mudéjar Seville, Spain  Dish with conical boss 15th century Mudéjar Machado de Castro National Museum Coimbra, Portugal |