Name of Monument:

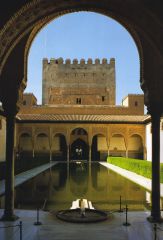

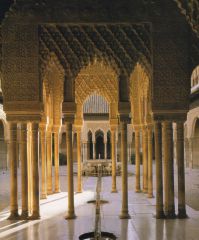

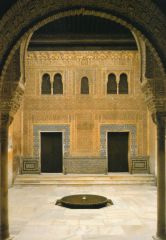

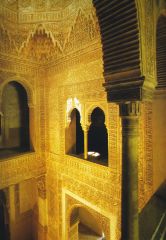

Alhambra

Location:

Calle Real de la Alhambra, s/n, Granada, Spain

Date of Monument:

From Hegira 636 / AD 1238 to the reign of Muhammad V (AH 754–94 / AD 1354–91)

Period / Dynasty:

Nasrid

Patron(s):

Muhammad I (r. AH 636–72 / AD 1238–73) built the Nasrid citadel; Muhammad II (r. AH 672–702 / AD 1273–1302) transformed the fortress into a palatine city; Muhammad III (r. AH 702–9 / AD 1302–9) built the Partal, the royal mosque and the baths; the remaining work was commissioned by Yusuf I (r. AH 733–54 / AD 1333–54) and in particular his son Muhammad V (r. AH 754–94 / AD 1354–91), who is responsible for the current physiognomy of the Alhambra.

History:

The successors to Muhammad V brought an inexorable decline in Nasrid art. Following the conquest of Granada in 898 / 1492, the Catholic Kings declared the Alhambra to be a royal residence. In 1526, Charles V decided to build the palace that bears his name, in a Renaissance style. The complex was declared a national monument in 1870 and is currently managed by the Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife, now under the auspices of the regional government of Andalusia.

Description:

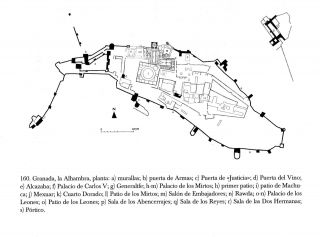

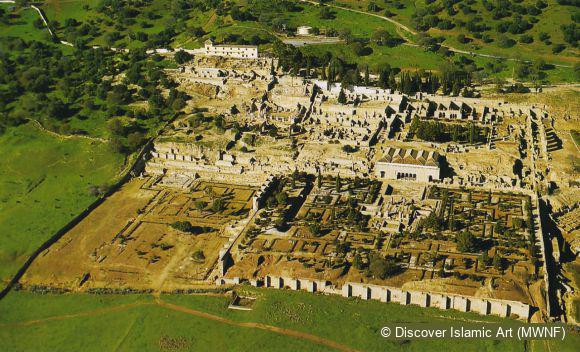

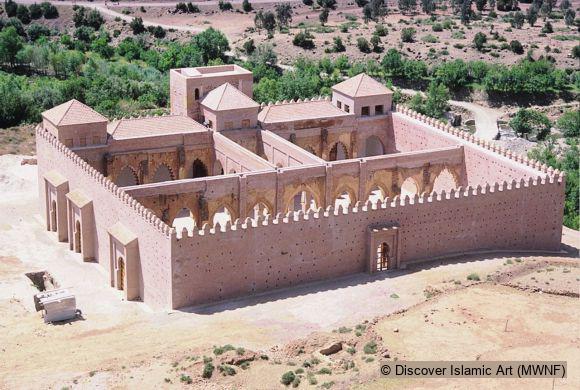

The name 'Alhambra' appears towards the end of the 9th century in a variety of different forms, the most common being al-Qalat al-Hamra, 'the red castle' due to the colour of the clay used in the walls. The complex is divided into three areas: the citadel, the palace area and the medina, in addition to the structures outside the walls. It has four large gateways to the outside, two to the north and two to the south, in the Almohad tradition, the most monumental of which is the Gateway of Justice, which dates from the early AH 8th / AD 14th century. There are two types of tower in the complex: residential (the Tower of the Captive and the Tower of the Princesses) and defensive (Muhammad's Tower and the Tower of the Lamp). The main through routes are the Lower Royal Road for access to the palace area, the Upper Royal Road, the main street in the medina, and the Circular or Ditch Road, the main thoroughfare.

The palace area constitutes a single unit, even though the seven palaces are separate. It should be remembered that the Alhambra as we know it today dates mainly to the second half of the AH 8th / AD 14th century with significant later modifications. Four buildings were virtually destroyed between 1492 and 1812, while the Comares Palace and the Palace of the Lions were conserved as an annex to the unfinished Renaissance palace of Charles V.

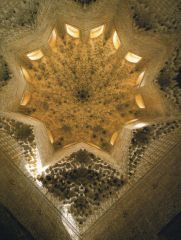

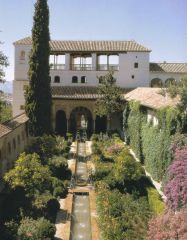

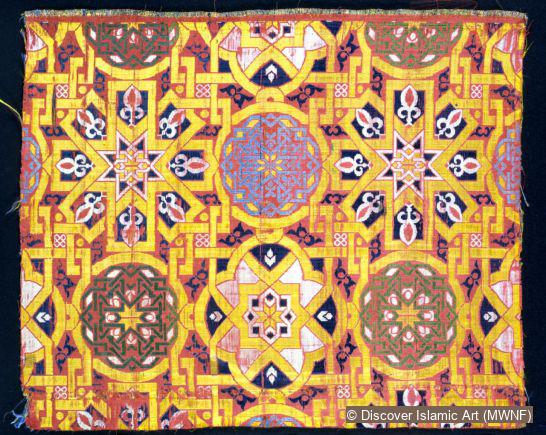

The Comares Palace was the official seat of the sovereign, and its principal function was to house the executive power. Its Court of the Myrtle Trees was the centre of a group of courts with bureaucratic functions that progressively revealed the presence of the king, who appeared publicly in the Golden Hall and the Palace of Justice (the Mexuar), and privately in the Hall of Ambassadors with its floor of white and blue tiles with golden decoration, now lost. The Alhambra is unique in the Muslim world for its floor tiles that bear the eulogy 'There is no conqueror but God'. The ceiling of this hall is a schematic representation of the seven heavens of the Muslim cosmos (Qur'an 67: 3). The Comares Palace had an interior façade on the south side of the court of the Golden Hall, the most profusely decorated wall in the whole of the Alhambra. The twin doors were designed to confuse potential assailants. The Palace of the Lions, a recreational villa, could be reached by a road and its Halls – of the Mozarabe, of the Kings, of the Two Sisters (summer) and of the Abencerrajes (winter) – were arranged around a court with intersecting axes, the first two halls being used for parties and banquets and the latter two for musical evenings, judging by their acoustics. It is possible that the king also used the Daraxa Balcony, which projected from the Hall of the Mullioned Windows over the court of the same name. Its honeycombed cupola is the most exuberant exaltation of Granadan art.

A road separated these areas from the Rauda (rawda, garden), the royal necropolis, laid out like a garden in Paradise. The Alhambra would not make sense without its gardens, which represent the culmination of a long tradition, some integrated with the architecture, for example, the Patio of the Lions and the Generalife, and others reaching to the very bottom of the hill. It is the only Andalusian palace with a set of inscriptions that explain the architecture and gardens.

For more than 250 years, this palatine city was the seat of the Nasrid Sultanate of Granada and the last Muslim stronghold in the Iberian Peninsula. Located on top of a rise in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, it was surrounded by more than 1,730 m of wall and several monumental gateways. It was divided between four main centres: the citadel, the palaces, the medina and the Generalife, a place of recreation.

It reached the peak of its architectural and decorative splendour under Sultan Yusuf I and his son Sultan Muhammad V with the Comares Palace and the Palace of the Lions.

How Monument was dated:

In addition to chronological references, a number of poems inscribed in the wall for different reasons help with dating, for example the poem in the Hall of the Two Sisters.

Selected bibliography:

Al-Andalus: Las Artes Islámicas en España, Exhibition catalogue, Granada, 1992.

Cabanelas Rodríguez, D., El Techo del Salón de Comares en la Alhambra: Decoración, Policromía, Simbolismo y Etimología, Granada, 1988.

Fernández Puertas, A., The Alhambra,Vol. I: From the Ninth Century to Yusuf I (1354), London, 1997; Vol. II: Muhammad V, 1354–1391, forthcoming; Vol. III: From 1391 to the Present Day, forthcoming.

Grabar, O., La Alhambra: Iconografía, Formas y Valores, 3rd edition, Madrid, 1984.

Torres Balbás, L., La Alhambra y el Generalife, Madrid, 1953.

Citation of this web page:

Ángela Franco "Alhambra" in Discover Islamic Art, Museum With No Frontiers, 2025. 2025.

https://islamicart.museumwnf.org/database_item.php?id=monument;ISL;es;Mon01;15;en

Prepared by: Ángela FrancoÁngela Franco

Ángela Franco es Jefa del Departamento de Antigüedades Medievales en el Museo Arqueológico Nacional.

Obtuvo el Grado de Doctor por la Universidad Complutense de Madrid con la tesis Escultura gótica en León y provincia, premiada y publicada parcialmente (Madrid, 1976; reed. León, 1998); y la Diplomatura en Paleografía y Archivística por la Scuola Vaticana di Paleografia, Diplomatica e Archivistica, con la tesis L'Archivio paleografico italiano: indici dei manoscritti, publicada en castellano (Madrid, 1985). Becas de investigación: beca posdoctoral del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores, Academia Española de Bellas Artes de Roma (1974-75); beca posdoctoral del Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia, Academia Española de Bellas Artes de Roma (1975-77); beca de la Fundación Juan March de Madrid (1978).

Tiene en su haber 202 publicaciones, fundamentalmente sobre arte medieval cristiano, en especial la iconografía: Crucifijo gótico doloroso, Doble Credo, Danzas de la Muerte, temática bíblica en relación con la liturgia (el Génesis y el Éxodo en relación con la vigilia Pascual) o con el teatro (Secundum legem debet mori, sobre el “pozo de Moisés” de la cartuja de Dijon). Es autora de cuatro catálogos monográficos del Museo Arqueológico Nacional, entre ellos el de Dedales islámicos (Madrid, 1993), y de publicaciones sobre escultura gótica y pintura en la catedral de León y sobre escultura gótica en Ávila, así como de numerosas fichas para catálogos de exposiciones.

Ha participado en innumerables congresos nacionales e internacionales, presentando ponencias y mesas redondas, y ha dirigido cursos y ciclos de conferencias. Es Secretaria de Publicaciones en el Museo Arqueológico Nacional desde 1989.

Copyedited by: Rosalía AllerRosalía Aller

Rosalía Aller Maisonnave, licenciada en Letras (Universidad Católica del Uruguay), y en Filología Hispánica y magíster en Gestión Cultural de Música, Teatro y Danza (Universidad Complutense de Madrid), ha obtenido becas de la Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional y la Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia de Madrid, así como el Diplôme de Langue Française (Alliance Française), el Certificate of Proficiency in English (University of Cambridge) y el Certificado Superior en inglés y francés (Escuela Oficial de Idiomas de Madrid). Profesora de Estética de la Poesía y Teoría Literaria en la Universidad Católica del Uruguay, actualmente es docente de Lengua Castellana y Literatura en institutos de Enseñanza Secundaria y formación del profesorado en Madrid. Desde 1983, ha realizado traducción y edición de textos en Automated Training Systems, Applied Learning International, Videobanco Formación y El Derecho Editores. Integra el equipo de Museo Sin Fronteras desde 1999 y ha colaborado en la revisión de los catálogos de “El Arte Islámico en el Mediterráneo”. Así mismo, ha realizado publicaciones sobre temas literarios y didácticos, ha dictado conferencias y ha participado en recitales poéticos.

Translation by: Laurence Nunny

Translation copyedited by: Monica Allen

MWNF Working Number: SP 19

RELATED CONTENT

Related monuments

Islamic Dynasties / Period

On display in

Exhibition(s)

Discover Islamic Art

Geometric Decoration | Geometric Decoration in Architecture The Muslim West | Seats of Power: Palaces Water | Water and Everyday LifeDownload

As PDF (including images) As Word (text only)

Back

Back